Can You Afford “Dehydration”?

©Arlene R. Taylor, PhD

My phone vibrated—in a meeting. I let it go to voice mail. It came to life twice more in rapid succession, so I stepped out and took the call. It was a local Emergency Department. One of my life-time best friends wanted to see me.

My phone vibrated—in a meeting. I let it go to voice mail. It came to life twice more in rapid succession, so I stepped out and took the call. It was a local Emergency Department. One of my life-time best friends wanted to see me.

“Good grief!” I exclaimed when the nurse had ushered me to Andrew’s cubicle. “What landed you in the ED?”

“Dehydration,” he responded weakly. “You know the temperatures have been in triple digits for several days. Because it is such a dry heat, I did not realize I must have still been sweating and that it evaporated almost instantly. I have the grand-daddy of all headaches. Collapsed in the front yard, I did. Fortunately, my neighbor called 911!”

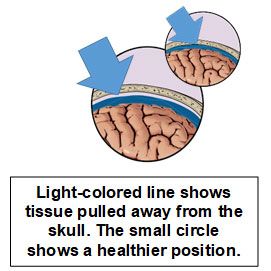

Truth be told, Andrew did look pathetic. Two IVs were running, one in each arm, replacing much needed fluid’s. Still dark circles under his eyes. “The ED Physician said that my brain tissue is pulling away from my skull. Did you know that brain dehydration has been found to contribute to dementia?” he asked, then quickly added, “What am I thinking? You are a brain function specialist. Apparently, people die from dehydration. I thought it only reduced your amount of urine,” Andrew mumbled.”

“Only?” I asked, chuckling. “It is way more important than that. Dehydration impacts all brain-body systems—and can be especially lethal to brain function, slowing it down and interfering with vital processes. Even your bones need water. Without it, the birthing of critical new body cells can be impacted. Negatively, I might add.”

“Only?” I asked, chuckling. “It is way more important than that. Dehydration impacts all brain-body systems—and can be especially lethal to brain function, slowing it down and interfering with vital processes. Even your bones need water. Without it, the birthing of critical new body cells can be impacted. Negatively, I might add.”

A nurse bustled in. Efficiently replacing one of the IV bottles, she checked Andrew’s vital signs. “Is your blurry vision clearing up yet?” she asked.

Andrew nodded. “It is starting to. I only see one and a fourth of you now instead of twins. I had no idea that blurred vision could be a symptom of dehydration.” Andrew introduced me and told the nurse, “I think she is about to tell me that dehydration is very expensive in terms of brain-body functions.”

“Pay attention!” the nurse responded, which triggered some laughter. “You were in bad shape when the ambulance dropped you off!” She looked at me. “It took nearly a liter of fluid before he could even recall your name and phone number! Life-time best friends notwithstanding.” She bustled out of the room.

“Dehydration is linked with low blood volume, kidney failure, heat cramps, heatstroke, seizures due to electrolyte loss, and coma,” I explained. “The brain is roughly 75 percent water, but brain cells are closer to 85 percent. As dehydration disrupts the balance of water inside and outside brain cells—there should be more inside the cell than out—problems can arise with short-term memory and recall of long-term memory. Ability to perform mental arithmetic decreases as well (e.g., calculating whether sleeping for another 15 minutes will make you late to breakfast or work, making change at the store, figuring out costs, evaluating options, and so on.” All I received in response was a groan.

I continued. “A one (1) percent level of dehydration results in a five (5) percent reduction in cognitive function—do the math!—which can trigger forgetfulness and inability to focus, cause general difficulty getting things done, decrease productivity, increase mistakes and exacerbate accident proneness.”

“More,” Andrew said.

“More what?” I asked. “You already have two bottles running!”

“No, tell me more! Is your brain getting dehydrated?”

I laughed. “Okay, you are over 50.”

“Tell me something I don’t know. I’m way over 50.”

“As brain tissue shrinks, it pulls away from the skull and, yes, dehydration is linked with an increased risk for dementia.”

“Funny, I wasn’t even aware of being thirsty,” was Andrew’s next comment.

“Thirst may not be a reliable indication that your brain and body need water—for a couple of reasons. Growing up many fed babies when they became fussy. If the child was thirsty and not hungry, the child learned to want food for both thirst and hunger . . . many adults eat when they are actually thirsty, because they don’t recognize thirst as a separate sensation. In addition, a person’s thirst sensation tends to fall after the age 50. If you do sense thirst, your brain already is at a 1 percent dehydration level . . .”

“Which translates to a 5 percent decrease in cognitive ability," Andrew interrupted.

The ED Physician came by to say Andrew could go home. “You’re lucky. Another hour or so and you’d be looking at serious dysfunction of some body organs—and brain!”

On the way home, Andrew said, “I know you need to get back to work. Would you come over later and give me Part 2 about dehydration? I had absolutely no idea how important staying hydrated was for brain function! I wasn’t even thirsty and now I know a possible reason. I’ll spring for dinner in case a little bribe would help.”

I helped him into the house. He was still a bit wobbly. “Let’s just call dinner a bonus between friends. You know I am not very bribable. See you later.”

I could hear him laughing as I walked out to my car.