Can I Have a Drink?

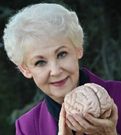

©Arlene R. Taylor PhD www.arlenetaylor.org

Okay, my mother (the language teacher) would have corrected the grammar to: “May I have a drink?”

Okay, my mother (the language teacher) would have corrected the grammar to: “May I have a drink?”

Nevertheless, how many times have you been asked a version of that question by children and grandchildren, nieces and nephews? Too many to count! Your response can impact the child’s brain and immune system—positively or negatively.

In 1980 study, the Water Research Council in Britain found that tap water constituted about 50 percent of the total fluid intake of participant groups (1-4 year olds and 5-11 year olds). A very small proportion of soft drinks were being consumed by these age groups.

Fast forward fifteen years to a similar survey by Petter, a fourth year student at Southampton Medical School. Parents kept a diary of all drinks consumed by their child over a period of 48 hours. The results in 1995 showed a very different pattern from 1980:

- 72 percent of preschool children ages 2.1 to 4.3 years and 50 percent of school children ages 5.5 to 7.0 never drank plain water during the study period

- In general, plain water had been replaced by carbonates, soft drinks, fruit juices, fruit flavored drinks, and other surgery drinks.

Of concern is that replacing plain water with other drinks, especially soft drinks, appears to have significant nutritional implications. In the youngest group these can include failure to thrive and bowel disturbances; in the older school children, diminished appetite resulting in missed nutrients at mealtimes, obesity, and dental caries.

Children are a targeted group for soft-drink advertising—some of which are even marketed as “health drinks”—and are being conditioned against drinking plain water. This is reinforced when parents and teachers role-model juice or soft drinks as their beverage of choice. Because the body needs water to process surgery drinks, the children may actually become dehydrated.

Mild dehydration can produce symptoms such as light-headedness, dizziness, headaches, tiredness, reduced alertness and ability to concentrate, and a preference for a high fat diet. Chronic dehydration can lead to a variety of health problems and illnesses including urine infections, bed wetting, constipation and increased risk for colorectal cancer. Even a small amount of dehydration in a child can lead to a reduction in mental and physical performance, including reduced concentration in the classroom along with potentially less participation and lower test scores.

According to the American Dietetic Association, children can easily become dehydrated during warm weather and/or through physical activity. In general, they:

- Do not tolerate temperature extremes as well as adults

- Have less sensitive thirst responses

- Produce more heat but acclimate to heat more slowly

- Have less well-developed kidney function and sweating ability

- Have a larger surface area to body mass ratio so are more likely to lose water by evaporation

Obesity in children continues to rise, placing them at higher risk for type2 diabetes and heart disease. The high sugar content of soft drinks has been identified as a contributing factor (and there are concerns about what sugar substitutes may do to the brain). Sugary drinks may not quench thirst as well as water does, either, so children may want to drink even more of them. What can you do to help?

- Keep no sugary drinks in your home. Replacing soft drinks and fruit drinks with water (e.g., no calories) can help children with weight control.

- Role-model drinking water on a regular basis (before you experience thirst).

- Provide pure water in fancy glasses before children go out to play or engage in sports activities and send water with them so they can remain hydrated throughout the day.

- Encourage children to study water and its related health benefits, especially if they need to do a science project for school.

“Can I have a drink?” That question again, this time from a little guy who was visiting with his parents.

“Certainly,” I replied. A bit of pouting—actually quite a bit of pouting—followed when he realized there were no soft drinks or fruit juices or sugary drinks in my refrigerator.

“But what do you drink?” he wailed.

“The best water in town,” I said, proudly.

He eyed my new machine, his little face twisted into complete skepticism. Soon, however, he was standing on a stool by the kitchen sink and holding a cut-glass tumbler under the spout. His mother had rushed to substitute a plastic cup but I had intervened, explaining that water tastes better in cut-glass… you should have seen his expression! A sip or two and the look on his face changed to one of surprise and he said, “Oo-o-oh. More. This is so smoooooooth!”

Over the next three hours, the little guy drank nearly a liter of alkaline water. Maybe he was intrigued with the equipment, maybe he had a visual sensory preference and loved the cut glass, maybe he was highly kinesthetic and exquisitely sensitive to taste. However, since he made only one trip to the toilet during the same time period, my guess is that he was very thirsty and probably dehydrated.

Bottom line?

Children need water—maybe even more so than adults. Your role-modeling and encouragement can have a huge impact on whether or not they drink plenty of water and learn to prefer it to soft drinks. And, yes, preventing dehydration can have an impact on their health, performance, and success at home and at school. You can give them a healthier future!